Young Critics Review: All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt

In a very wide shot, a young woman is standing on a leafless tree with prominent branches. Her name is Mack. At the bottom, and some meters apart, there is Wood, her beau. They are distant, but somehow their conversation shows proximity. Wood asks Mack to go swimming. She refuses because she doesn’t know how. “My dad just threw me to the water. That’s the best way to learn, he said”, Wood tells her. When she asks what happened he laconically replies, “I sank”. The scene is from Raven Jackson’s All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt, a film that is build up mainly with close-ups. This wide shot, thus, is distinctive, and thanks to its distinctiveness, some of the film’s subjects are elicited.

Most of the exchanges between these youths deals with learning. Be it how to catch a fish with a rod and how to cut it afterwards or how to raise a baby, the obtention of knowledge occupies much of the film’s length. But learning doesn’t come for free. As the dialogue implies, there are certain risks, like dying or losing someone. Despite them, you must live, no matter how painful this may be. The film follows different generations of Mack’s family, where deaths and losses are present. Not surprising, nor a minor detail that in the middle of that key shot, there stands a tree: this is a film about genealogies.

Births, first kisses, dancing couples, and funerals –the life defining moments of any family– are scattered in ninety minutes of neat, lyrical images. The narrative is not chronological which conveys a sense of confusion and indeterminacy that is supported by several formal devices. Jackson privileges the use of lingering close-ups. What do you get when you look too close at something? A sense of detail, of intimacy, of deep knowledge. With this, the broad picture that allows us to understand the set of relationships within a specific setting is lost. Jackson choses closeness above context to gain in affection. Several shots are close-ups that show the characters holding hands. The framing allows to look at the careful and warm way in which they touch. However, this magnification. isolates the filmed subject from its environment. In this way, the specific relationships that the characters have and their inner lives, although they share the same blood, remain a secret.

In some scenes, Mack is shown at different ages and in some moments, we see either her mother or grandmother. Thanks to the close-ups and to the fact that the characters’ names are barely said; the different branches of the genalogical tree interwind. The deliberate vagueness in the narrative that results from it emphasizes gestures: the act of touching for touching’s sake, which provides a sensation of togetherness where characters handle loss and pain. Losses, in consequences, are not addressed directly. Who died, who left, for what reason, and what was the relationship that the character on screen had with the departed remains unclear. But there is truth in a shimmering tear that waters the face like rain does the earth. Physical touch among the characters becomes an accompaniment which helps to cope with sorrow, to “master the art of losing”, as Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art” refrains.

The joys and pains a family go through remain from one generation to other: their prevalence erases past, present, and future. “Water doesn’t end nor begins, it changes form” is uttered at some point in the film. The transformations implied in that statement summarizes this familiar story and can be noticed in the delicate film’s sound design. The hubbub of fire burning in a house, the clatter of raindrops falling to the ground, and the loud grasshopper’s chant sound in the same way, rhyming together images that are apart. The source of these sounds is different, but their harmony is the same. This provokes a feeling of unity as the one that comes from holding hands: the correspondences are some sort of embrace that creates safety out of noise. The film is full of rather harsh situations, but Jackson’s poetic style makes them bearable. All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt yet there is some sweetness in them.

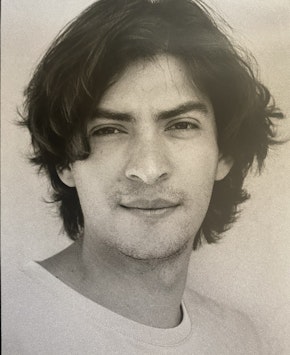

José Emilio González

José Emilio González is a Mexican cinephile. His texts are published in outlets like El cine probablemente, Correspondencias, Butaca Ancha and photogénie. He majored in English Literature; his thesis degree was about Matías Piñeiro and Shakespeare. In 2021, José Emilio González was a part of the Young Jury at Black Canvas, and, last year, he participated in the Guadalajara Talents Press. He is also the Programming Coordinator at Bogota International Shorts Film Festival (BOGOSHORTS).